A ‘like’ is only a click, but it helps enormously. It raises the profile of this piece. If this writing has value to you, remember that your ‘like’ has value to me. Thank you for the gift!

Dear Peter

I don’t blame you for dying. Let’s get that out of the way. I know you didn’t want to go. And I know you would have looked after me. In fact, I think you did, from beyond the grave. Or let’s be real; from beyond the crematorium chimney. Because they never put you anywhere. And that’s how you ended up everywhere. But also, for me then, painfully absent. You left a hole that I didn’t know how to fill.

I’m going to tell you this story. It’s addressed to you, but I shan’t sign off.

I met him at work. He was not my type. But he was sociable. Friendly. A big presence with a booming voice. Years later, after the whole story unfolded, when people asked me how I ended up with him, I’d say, “I was mentally ill.” The snap answer, the funny answer, you’d approve. An easy deflection to save me from going into details. But I reread my diaries from the year I met him, and it wasn’t so far from the truth.

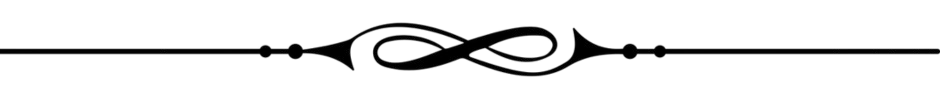

When I started my short career as a computer programmer, I was only a couple of years out from a breakdown. There was plenty of backdrop, not least your death from cancer. When you were diagnosed at sixteen; they said if you made it to eighteen, you’d go the distance. You died three weeks before your eighteenth birthday. In January 1984, approaching my twentieth, and the fifth anniversary of your death, I spiralled into a serious bout of depression. The cause, to anyone else, looked like nothing.

A month before, at a Christmas party in the university’s main hall, I slipped on some porridge thrown onto the floor for a dancing challenge. Who can stay on their feet? asked the DJ. Not me. Not anyone. I found myself writhing in oat goo with one of the in-crowd, Dominic. He was an ‘80s mod, a Northern Soul dancer, too cool for my mess.

But my outside and inside didn’t match. He didn’t know I was a mess beyond the porridge, the dress that never recovered in dry-cleaning. My look was like his: sexy, a little icy. One dancefloor slip and we seemingly fell for each other. A rapid intensity. Private jokes, private language, private phone calls. A short separation while each of us went to our folks’. Three weeks later, drunk at a London party, he pulled me out under the stars to tell me he loved me. We hugged on the frost-bitten grass. But I must have responded wrongly. Too much relief, perhaps. The last person to make me feel I was loved was you. It had been a long time since I felt valued.

The next morning, the temperature dropped. We spent the day like tourists, returning to our university town in the evening to meet with his (very cool) friends. When they asked what he’d been up to, I twigged the pronoun shift. He used “I” in all the places where “We” was the truth, cutting me out of his account. When I was there, right there at his shoulder.

For two or three hours, I sat with him and his friends, slowly dissolving. They had their own in-jokes. “We” didn’t exist. When I challenged his coldness — perhaps following him to the bar to speak to him alone — his response was, It’s over. The day before, he’d “loved” me. Now, I was done.

At five minutes to midnight on New Year’s Eve 1983, I crossed the city centre park called The Level in floods of tears. He’d not been on the level. I couldn’t understand what had happened. And then it was midnight; the nearby pubs exploding into Happy New Year! and the drunken singing of Auld Lang Syne, and I knew they’d be kissing each other and I, yet again, kissing no one.

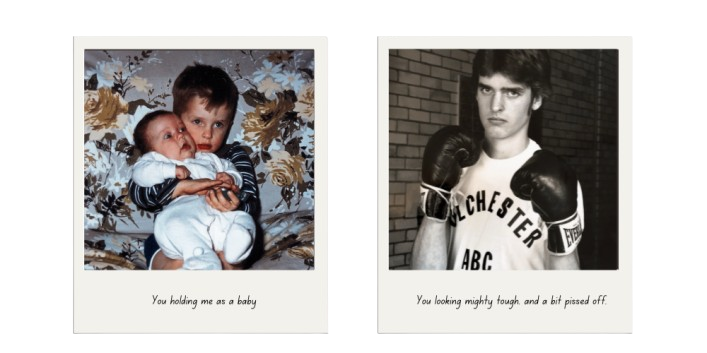

January had become a terrible month, since you died. It was the month where I’d seen you for the last time trying to climb the stairs, all skeleton. The month where I’d stood at your bedroom door, time after time failing to go in, afraid of the tears that started swimming to the surface, unable to pretend you weren’t dying. The month where I dreamt you kissed me by a swimming pool, weird for a brother and sister who related through jokes and piss-takes, and all the next day at school, I kept thinking that kiss felt like goodbye until I couldn’t stay another minute, and asked to be excused in PE. I ran home through the snow-whitened lanes in my yellow hat and yellow gloves, my yellow scarf streaming out behind me, out of breath through the alley, until I reached our road, turned the corner, and saw Mum standing at the open door. She told me you were in a coma. Had been in a coma since last night.

Finally, I could go into your room next to mine in the basement and sit beside your bed because it didn’t matter anymore if I cried. You had the lower bunkbed, under Doug’s. Had been caught in it having sex with two girls at once only a few months before. But we were still children, really. I remember looking at the apple core on the chair placed next to your bed to be a kind of bedside table and thinking there it is, the last thing you’ll ever eat. Your breathing came with bigger and bigger gaps. It looked a bit like you were smiling. I told you I loved you, which I could never have told you to your piss-taking face.

Then my turn was over, the next of us siblings came to sit with you, and I went upstairs, hungry as usual. You died while I was eating a bowl of cereal, which I found hard to forgive about myself. It seemed so inappropriate. Six days later it was my 15th birthday. As you can imagine, it wasn’t a happy one. And on the final day of the month, it was your funeral, delayed by strikes in the Winter of Discontent.

So January was a hard month. And my powerful brand new “love” dissolving just as January came? It tipped me over the edge.

I was used to being shouted at in the street, but now I couldn’t take it. Someone shouted, “Oy, blondie, give us a blow job!” and I changed course, went straight to Fred the Barber’s and asked him to shave my head. It cost 99p. I sat on the beach for hours until so frozen I could hardly move. Watching the waves, unable to get up the courage to just wade in. For other hours, in the café I knew to be Snow’s from Brighton Rock, I wrote and wrote and wrote. Trying to make sense of the mess of myself. Trying to find the courage to end the unbearable pain.

But somehow, always, your death made it impossible. What an insult to you to end my life voluntarily when you would have given anything to live for just one more day, however shitty. So I dragged myself though January. I went to the clubs and danced. I met someone I didn’t care about and let him do what he wanted to me; lay there like the mattress. After three weeks with him, during which time, I became homeless — weirdly, because of leaving a porridge pan to soak — I met his friend.

His friend, in the year above me at uni, was into therapy. We got together, and I got into therapy too. The free kind, provided by counselling students, which frankly, had its own drawbacks. But after a year of that, at least I had clarity. I wasn’t any less fucked up, but at least I understood why I was.

After graduation, I spent a year trying to “be a writer”. I made forty quid, selling four poems to Faber and Faber, appearing in their anthology of young British poets, Hard Lines 3. The highlight was the launch at Riverside Studios. Ian Dury was there. It was you who’d introduced me to his music. Played New Boots and Panties!! very loud on our stepfather’s fancy stereo when they were out. Ian Dury crossed the room towards me. Asked for a drag of my cigarette, bum-sucked it, and gave it back. I was too star-stuck to speak. A newspaper review of the book was pinned to a noticeboard. The first literary mention of my name. A single sentence: “Ros Barber takes no shit.”

Excellent, but not exactly true. The poems, perhaps, were flinty, like the carapace Dominic had thought he was in love with. The poems were hard. They took no shit. But Ros Barber, in fact, was primed for taking shit.

Indeed, the current “nice” boyfriend wasn’t doing nearly a good enough job of dishing it out. Sure, he had some issues, not least that he preferred sex with his hand than with me. Which wasn’t doing wonders for my self-esteem. But he was much better to me than I felt I deserved.

Having made only forty pounds from my year “as a writer” on top of unemployment benefit, I realised that the biggest problem with trying to be a writer at the age of 21 was I hadn’t lived. I needed material. Plus, didn’t I owe it to you, brother, to actually live? Not just sit in my bedsit, trying to write, and taking long walks to avoid my own inadequacy. What did I know about life? Barely a thing. But I was about to learn a whole lot.

I started temping, but that wasn’t living either. Then I got an idea: I would buy an around-the-world ticket. For that, I’d need a proper job. And the proper job fell into my lap. One lunchtime, the other temp read out an advert in the local paper as a joke. Graduates in any discipline. If you pass an aptitude test, we will train you in computer programming and systems analysis. I laughed along with her. But on the way home, I picked up a paper and applied.

I met him at work. He was not my type.

Backstage pass bonus below the paywall. Thank you for being here. Have a good week!

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to How to Evolve to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.