Half the time at the moment, I’m channeling the spirit of 18th-century pirate Mary Read (or re-channelling, since I’m in the last two weeks of the third novel’s second draft). The rest of the time I’m writing academic sentences about obscure Elizabethan epigrams. (And avoiding doing my US tax return, which as an accidental American, whose dad helped the buggers get to the moon, feels like an unjust penalty for humankind’s advancement.) Every morning, I’m also journaling; personal and reflexive writing that feeds my Substack posts.

This week, “Your Friend In Bagged Aggregates” (or any other dull-sounding comedy-friendly job title) is having a pre-flight Wetherspoons breakfast in the Departure Lounge before he jets to the Maldives, which he can afford because he has a “proper job”. I enjoyed processing my annoyance through him, but annoyance, like any brand of anger, is healthiest when swiftly eliminated. Finding myself in a more peaceful place, I’m mulling further on human evolution.

This is in response to one of the comments on my ‘humanifesto’ from a new subscriber, @nickherman. There have been a lot of new subscribers this week because I said something on a Substack Note about bookshops, sofas and cake, so thank you, welcome, grab a slice of Battenburg and a space on one of the Chesterfields. I hope we’ll get to know each other a bit, and kick some ideas around. (And I’m thinking now of the fantasy-yet-utterly-real library where I stayed in a VW Camper van in Amsterdam last year).

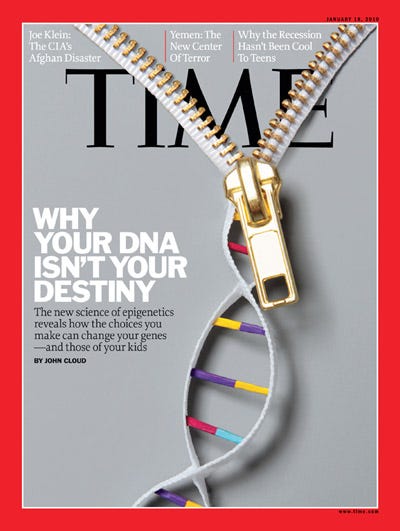

Nick mentioned epigenetics, and I said epigenetics is one of the reasons I am hopeful about the future of humanity. Let me explain. My first degree was in Biology. My final year specialisms were Evolution Theory, Animal Behaviour, Animal Psychology, and Genetics. It was the mid-1980s, and Richard Dawkins’ The Selfish Gene was pretty much The Bible for biologists. That book changed everything about the way we humans perceive ourselves. We’d spent over a century coming to terms with the fact that rather than being made in the image of God, we were simply advanced apes. B ut hell, we were pretty special apes. The Selfish Gene said, “Actually, you are even less important than that. You are vehicles for genes to replicate themselves, even in ways that aren’t to your benefit. You are basically a host to the parasite of your genes.”

Suddenly we were all victims of our genes. Sure, we’d known for decades that genes controlled things like eye colour, not important (unless you are Cillian Murphy). But now it seemed they controlled everything. What was the point of anything if your genes controlled your destiny? Your mum and cousin both had breast cancer? Bad luck. Your dad dropped dead at 40 from heart disease? Don’t make any long-term plans. The biologists set out to map the whole of the human genome, expecting to find genes that controlled every facet of ourselves, including personality and behaviour.

And while the scientists mapped, the general public took a little knowledge and, as is their way, turned it into a dangerous thing. We decided everything was genetic. If you were an arsehole, you probably couldn’t help it. No doubt being an arsehole was genetic. I mean, your father an arsehole, and look at you, being one too. No escape. I mean nature-nurture, sure, maybe you learned to be an arsehole from your dad, but everyone knows it’s really all about the genes.

Still, to this day, people will tell you there are genes for depression. None have been identified, although terms like ‘probably a combination of genes’ are bandied around. The medicalisation of habitual and paralysing misery justifies taking it seriously – which is useful – but also makes it inescapable. Some depressed people will defend this unproven idea vigorously. An imagined genetic cause validates their feeling of powerlessness. I’m sympathetic; I too have been there and thought escape impossible. But ‘imagined’ is the correct word here. And imagination, as writers know, is incredibly powerful. Like other power tools, it can build a beautiful staircase to a new level, or it can chop off your legs below the knee. Thoughtful handling is required. I love the Odd1sOut song “Life is Fun” featuring Boy in a Band, which my daughter introduced me to, but I have been known to shout ‘No it isn’t!’ at the genetic depression line, because it’s a terrible message to spread. “It’s genetic” = “no solution. You might as well give up.”

EPIgenetics, friends. That’s where it at. Plenty of people haven’t twigged this yet, but things in the world of genetics have moved on. What we’ve discovered (not me, but people I might have been had I not taken a diversion into English Literature by way of computer programming and an abusive marriage) is that we share 98.8% of our DNA with chimps. We’ve also learned that our 1.2% of human-specific DNA doesn’t contain the answers to the migraines you share with your sister, or your brother’s violence, or your son’s depression, or anything else. Epigenetics demonstrates that factors beyond your genes affect gene expression; in simple terms, whether genes are activated or not. Our genes are not, it turns out, the inescapable controlling force in our lives.

As a Dawkins apostle, reading Bruce Lipton’s The Biology of Belief blew my formerly predestined mind. I went to see Lipton speak in London and wept with joy on the train home (empty carriage, luckily). Here, at last, was a scientific reason for hope. Lipton was a cell biologist at Stanford University, and he relayed some exceptional discoveries. One of the things that turned my old biology world upside down was that the nucleus, the important-looking blob with all the DNA in it, is not the ‘brain’ of the cell. It’s the gonads. The ovaries/testicles of the cell, if you will. And the ‘brain’ of the cell? I can feel myself going down a different rabbit hole here, so I’ll backtrack.

The point is that our DNA isn’t the architect. It’s the blueprint. As with any blueprint, the architect can come along and rub out this wall, cantilever the window, put the staircase outside, and double the floor space. The architect can cause a different house to be built. The house is your health. And the architect, in large part, is you. What controls your gene expression can be summarised as “aspects of your environment.” And one of those aspects is your thoughts. There are those who are going to resist this kooky idea. What, the private conversations I have with myself in my head that no-one else is party to? Let me tell you who is party to them. Your body.

Years ago, when I was in therapeutic practice (I know, what can I say except “portfolio career”), I read another therapist’s account of a client who came to her in a wheelchair, though doctors had discovered no medical reason why her knees had given out. Nothing on the x-rays and scans, nothing in the blood tests. As the client unravelled her story, the therapist noticed that the woman kept saying “I can’t stand x”; “I can’t stand y.” Coincidence? Or had she just been incanting the negative affirmation “I Can’t Stand” for so long that her body had taken it literally? (If this story is familiar, that may be because I wove it into my novel Devotion; thanks for reading!)

Words are powerful, friends. There are reasons why curses are common tropes in folklore. Words have tangible effects on material things. Even those silent words in your head, your thoughts.

Want stronger evidence? (Anecdotal evidence is interesting but where’s my double-blind controlled trial, right? You’re my kind of person.) Let’s consider that extremely well-known phenomenon, the placebo effect. It is so well-recognised that every drug trial has to account for it, and even quite powerful chemicals can struggle to outdo the curative properties of a sugar pill. (Hell, maybe we should just prescribe everyone chocolate and a cuddle from someone who loves them three times a day). And what ‘controls’ the magical-seeming placebo effect? The patient’s belief they are receiving the real drug. Their thoughts.

Thoughts can, of course, be positive, neutral, or negative, so guess what. The negative correlate, the ‘nocebo’ effect, has also been documented. You can read a bunch of scientific papers about it. Or another more accessible summary, which includes cases where people have died because they believe they are going to. Which is pretty much how voodoo curses work. Except these voodoo curses are administered, more often than not, by qualified medical personnel. The problem is in their very authority. If an elderly lady knitting a scarf tells you you’ve got six weeks to live, you’ll be fine (unless you think she’s a witch). If a doctor tells you you’ve got six weeks to live, you’ll likely believe him. It is not uncommon for people to drop dead in exact concordance with their doctor’s prognosis. To the day. And we can do this to ourselves too: in a nocebo study on patients facing surgery, those with positive expectations had better outcomes — that is, were less likely to die — than those with negative ones.

The point is that there are really good reasons to keep focusing on what’s good in your life and retain as much positivity as possible. It materially affects your health. Long-term studies should be done to see if hours spent on Twitter positively correlate with a shorter lifespan. I’m betting yes. Being boiled in that soup of anger and despair can’t be good for anyone. And if you’re leaking negativity to those around you, consider it like smoking indoors. If you have to do it, take it outside. Sure, we all need to vent (see last week’s post). And every one of us can have a peanut morning. But commit to focusing on, and consuming, only the parts of life’s buffet table you want more of. Don’t, as they used to say on Usenet, feed the trolls. And that includes your internal ones.

After decades of Selfish Gene dogma, epigenetics puts our lives back into our hands. We have more agency than we realised. We are more than (1.2%) special apes. The tools at our disposal go well beyond a stick to poke ants out of a hole (I’m thinking of Twitter again). Humans have this extraordinary additional gift: the creative or destructive power of our own thoughts. Armed with the knowledge that our thoughts have material consequences (not least for our health and the health of others), we have the possibility, with conscious handling, to use our imaginations to build a beautiful staircase to another level. And knowing this, why would you want to do otherwise?

++ If you liked this post, touch the heart (gently) so more people can discover it.++

Sharing is also a wonderful way to spread a little light in this sometimes dark-seeming world.

Post-it Notes

Since last week I have

Edited 11,500 words of the novel

Been interviewed for an exciting article in The Guardian

Enjoyed a hilarious ‘premonition’ event with my daughter

Had a Substack Note go a bit viral, 1000+ likes

Welcomed 120 new subscribers, yes, hello! Thank you! I hope you enjoy hanging out with me.

Placebo or nocebo, that is the question. Was Hamlet (or the person behind him) before his time with epigenetics in describing nothing being either good or bad, but thinking makes it so? 🤔

Thanks for the shoutout. A friend of mine is a researcher in Huntington’s Disease and I was literally just reading some literature he sent me that was talking about the role of epigenetics, even though it’s pretty much a inheritable disease—but epigenetic factors seem to differentiate how quickly which types of brain cells are impacted/mutate/die within the disease’s progression. Essentially, I think the deeper point that was clearer to me even when I was an undergrad, is that biological systems are full of complex feedback loops, so perhaps it’s not surprising that our genes, brains, minds, or perceptions of ourselves should be any different in the end. As they say in Buddhism, “the self doesn’t exist, it’s a delusion,” and I think even pre-science, that was the result of powerful observation and introspection at work in terms of how we’re all interconnect and hyper complex beings, pure reductionism basically always fails in these cases.

Also, that van in the library haha what?

I’m an accidental American in the senses that it’s where I happened to be born after grandparents immigrated there (something I’ve been reflecting on more recently), and adopted made up names for assimilation purposes (I guess?), which I’m still carrying, like some strange genetic mutation. Now I live in Canada, so I also have to go through the same tax crap in 2 countries.