Love, Loss and Self-Sabotage: the Silent Deal that Shaped My Life

Happy Valentine's Day. For uplift, read to the end.

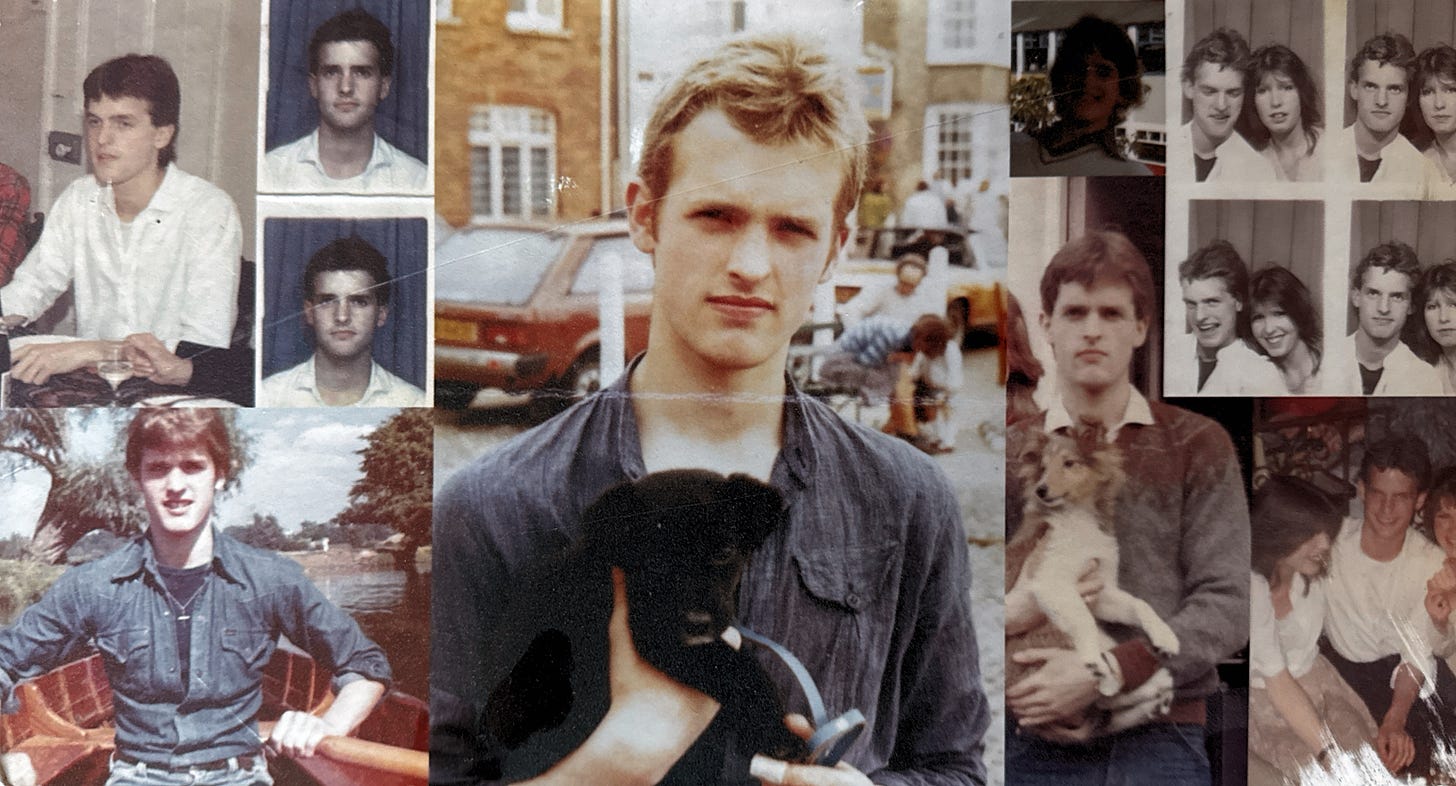

The girl is fourteen. She stands at her brother’s bedroom door, trying to hold herself together. He is in there, dying.

For days, she hasn’t seen him. For days, she’s been too scared to open the door. Several times, over several days, she’s stood there. It’s just Pete. She just has to knock.

But he’s dying. She doesn’t think she can hold it together. He needs her to hold it together. Sit beside him, watch telly with him, crack stupid jokes. He doesn’t need her crying, not now. But every time she gets to his door, the tears start. She cries, and she can’t go in.

The last time she saw him, that’s what did it. On the stairs, he looked like a skeleton. Skin over bone. He was gripping the bannister, trying to get himself up two floors to the bathroom. He wanted to do it himself. Didn’t want help. Didn’t want to shit in a bedpan.

But the cancer had wasted his muscles, those muscles he built as a rugby player, as a junior boxer. He could barely get himself up, step by step. That’s when she knew for sure she was going to lose him. Up until then, she could push it out of her head, even though the doctors had said before Christmas, six weeks. Even though it was six weeks now. That was the last time he got out of bed.

And now, each time she gets to his door, she cries. Which is not what he needs. The last thing he needs is her leaning on him for comfort, which she’s done for years. Like when she left home, stayed out all night on a doorstep, and nobody noticed. She sought him out at his Saturday job, cutting cheddar at the deli counter of British Home Stores. He served her brotherly advice. Called her ‘Sis’. The only person in the family who actually liked her. Who was always there for her, if he wasn’t out drinking, dancing, driving his metallic blue Mini. Soon he wouldn’t be there for her or anyone.

He needs her to be brave, and she’s failing.

She hears his music through the wall that separates their bedrooms. It used to be Ian Dury, Gang of Four. Now it’s Carol King’s You’ve Got a Friend, over and over: the song that is going to make her cry forever. And Elton John’s Song For Guy, which will play out his coffin. These are the songs that comfort him as he dies on morphine.

A few weeks ago, he could still get upstairs to the kitchen. He was writing a song. He said there was something wrong with his electric guitar. Sparks, he said. Sparks that looked like insects, crawling all over the neck and the strings. But it wasn’t the guitar. It was the morphine.

When he was diagnosed, at sixteen, with Ewing’s tumour — was operated on, had bone removed from his hip — had radiotherapy, chemo, lost all his hair — they gave him a seventy per cent chance of survival. Seventy per cent seemed hopeful. The doctors said it was a childhood cancer. If you live to eighteen, you’ll live to eighty. Taking them at their word, she’d been counting down to his eighteenth birthday. He was seventeen years and ten months old when the secondaries were found.

She never does open that door while her brother is conscious.

She never does go in to see him.

Instead, he comes to her, in a dream. For some reason she doesn’t understand, they are standing by a swimming pool. He kisses her strongly, full lips. An unusual kiss. She wakes up, feeling perturbed. She goes to school.

Throughout the day, she thinks about that kiss. Sitting on the floor in the sports hall in her PE shorts, it dawns on her what it felt like. It felt like goodbye. She asks to be excused. The teacher must sense this is real; doesn’t ask for a reason. She changes fast, with shaking fingers. Runs home through the snow-whitened lanes in her yellow hat and gloves, her yellow scarf streaming behind her. She sees herself like this, from the outside. Like a girl in a film. When she turns the corner into her road, their Mum is standing at the open door. Her brother has been in a coma since last night.

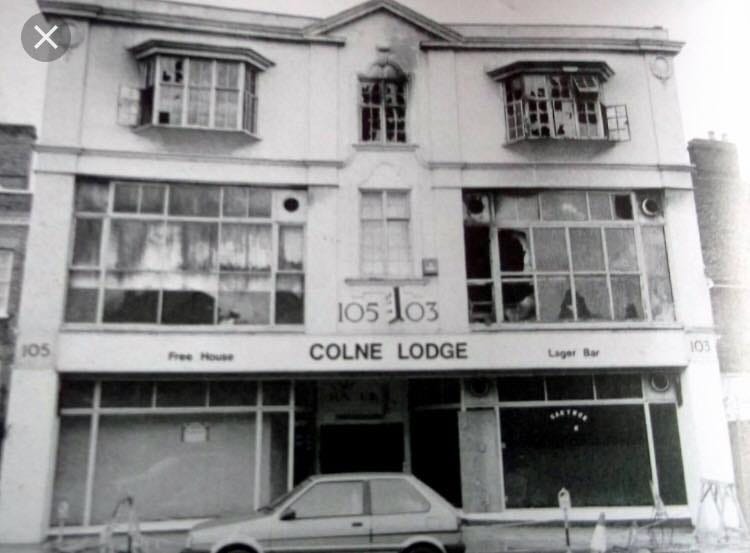

Finally, the girl can go into his room. Now it doesn’t matter that she’s crying. She sits by his bed, the lower bunk. Next to his bed, an apple core. The last thing he ate. A cigarette butt in an ashtray he stole from the Lodge.1 She takes the butt, slides it into the empty Rothman’s packet. She’ll keep it, that last thing that touched his lips.

His breathing rattles. The gaps between breaths lengthen. There’s a faint smile on his lips. She tells him she loves him, which she never could say to his face.

Her Mum comes in. It’s someone else’s turn. She goes upstairs. While she’s eating a bowl of cereal, he dies. That night, she babysits for a neighbour, as agreed. The next morning she goes to school. She’s afraid to stop pretending everything’s normal. Afraid of the howling gap. Six days after his death, she turns fifteen.

She writes the facts neatly in her lockable page-a-week diary. Messy emotion spills into her ‘extra’ journal: the exercise books she keeps for that purpose. She writes in colour-coded felt tips: red for anger, blue for sadness. She writes so furiously that it burns through the pages.

I will never get over this.

I will never get over this.

I will never get over this.

The girl is me, of course.

Decades ago.

But yesterday, I discovered something new. Something that has shaped the whole of my life, in secret. I’ve written about the power of vows before. And it turns out I've spent my whole adult life in thrall to a teenage pact.

Losing my job last July has been a top-quality personal development course. The need to stay buoyant while attempting to replace my salary with multiple possible freelance income strands, many of which go nowhere, has been … challenging. There is only so far my redundancy money will take me. Substack has helped a bit. But only a bit.

Hence, a new pivot, rejoining LinkedIn.2 Offering something that nobody understands. I can’t afford to drop that attempt, not yet. But I’m hitting a wall of internal resistance.

So I tapped3 on my feelings about LinkedIn. Yes it’s hurting me to be there when, in truth, I just want to write. To get paid for what I do best, in a world where I belong. Which is the literary world, not the corporate one. But I could tell that something else was going on.

Why do I hate LinkedIn so much? I wondered. Because my resistance grew strong and visceral. More than distaste. Almost an allergy. Tapping brought the answer to the surface like seagulls’ feet bring up worms after rain. LinkedIn? It feels like secondary school. All the kudos, expertise and respect I've gained in other areas vanish on LinkedIn. I’m back to being that weirdo. I don’t fit in.

A wave of emotion surfaced: me at 14, 15, 16 years old in a school full of people who saw me as weird. I tapped till the wave had subsided, and in the peace that followed, I instinctively found myself tapping a positive statement. The one that arose was simple: “I choose to thrive.”

I choose to thrive.

But why was this making me cry? Why was emotion rising again, a wall of sadness I could barely fathom? The answer surfaced. Peter. What was it to do with Peter?

And then I realised. I had made a pact with myself, when Peter died, that I would not thrive. That I would NEVER RECOVER from his death. Because I had lost him, and if I thrived anyway, that would mean, in some sense, he didn't matter to me, that I didn't feel the loss of him. Teenage logic. Locked in for decades.

And haven’t I been a good sister? In my early twenties: financial success but emotional mess. Three years of good money before sinking myself into an abusive marriage that would strip away everything. Ever since I left, dragging three kids in my wake, I have also dragged debt. As soon as I’ve had some success,4 I’ve backed off and failed to capitalise. I flirt with visibility — something happens5 — I dive into obscurity.

Always striving, not thriving. There was something I couldn’t see or name, always holding me back, an invisible chain. And yesterday, I found it.

This was huge. I tapped and tapped and wept. Undid the vow. Undid the pact I made with myself not to thrive. Fuck, it made total sense! Time and again, I have held myself back at the brink of a life I dream of. Yet Peter would want me to thrive.

I undid the pact. I said, Even though Pete died, and I miss him, I choose to thrive in health, wealth and happiness. I tapped and tapped until it felt released.

Double bonus: I decided not to kick myself for only just finding out. I suspect the timing is perfect. Striving to survive led to my becoming a polymath as I thrashed about, looking for release from my self-created bonds. I got a Biology Degree. Learned programming. Became a therapist. Did a PhD in English Lit, and learned critical thinking. Wrote a poem that is studied by thousands.6 Wrote a prizewinning novel.7 Became an academic, publishing in three different disciplines.8 Got very good at teaching. And of great significance, had a spiritual awakening. Supported my kids and their friends and their partners. Kept my second marriage together for nearly quarter of a century and counting. Paid all of the bills, for six of us, for twenty years.

Had I not been strangling my success, had I won through earlier, I wouldn’t have half of these strings to my bow. I would have much less to offer the world.

Here we are, humanity in crisis. A world that would have sunk me years ago, but now? I can swim. Can teach others to swim. Right now is the perfect time to release the pull-pin that allows me, at last, to thrive with momentum. Because this is the time my accumulated skills are most needed. So, onward.

Some love is for a lifetime. The absence of the person you love feels like torture. We should not forget that St. Valentine was tortured. That his love for humanity endured — that he sent a letter of love to his torturer’s daughter. And don’t we all understand? Love is the most powerful driving force that exists. It is who we are, at our centre. It is what we were born to be.

If anyone seems like the opposite of love, they are lost. For whatever purpose they serve: to shake us out of complacency, to help us clarify the world we want, they have cut off from the heart of themselves, in a spiritual fugue. But they can’t conquer love. Because love endures even through death.

It is time that we who are not lost turn up the love so that others can find us and join hands. It is time to find the rusty old pull-pins that keep us from thriving and release ourselves into the flow.

Look for yours. Give it a tug. This is me, signing off, sending love.

++ If you liked this, LIKE this 💜. Thank you! ++

P.S. I did a tapping demo on video for paid subscribers this week: it’s here if you want to try it for yourself!

The Colne Lodge was where we all drank (underage). I was drinking vodka and lime there, aged 14. Not long after I left my home town, there was a fire. It never reopened. The coolest pub in Colchester was turned into an “alzheimer’s friendly” care home. The place is still fondly remembered; the Colchester Colne Lodge Remembrance Group has nearly 600 members.

If you are a good-hearted human, connect with me here: https://www.linkedin.com/in/ros-barber/.

Probably my biggest success: https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/entertainment-arts-23080170

My very first time writing for a Guardian, an opinion piece I thought jocular, caused such a pile-on that I never took up the Book Editor’s invitation to write more for them: https://www.theguardian.com/books/booksblog/2016/mar/21/for-me-traditional-publishing-means-poverty-but-self-publish-no-way

See footnote 4 ;-)

This was the most powerfully moving piece I’ve read in a long time, Ros. I’m thrilled for you that you came to this realization. I’m going to do some deep soul-searching today,

Ros,

This hit like a freight train wrapped in poetry. The weight of loss, the silent contracts we make with ourselves, the way grief can shape us into something we never intended but somehow still became. It’s staggering how one moment—one vow—can echo through decades and how undoing it can feel like opening a door we didn’t realize we locked.

There’s something powerful about this timing, though. The slow burn of realization, the years spent gathering skills, understanding, and perspective—maybe that’s what was needed to make this release truly stick. Because thriving now, with all of this hard-won wisdom? That’s a different kind of thriving. The kind that carries weight.

So here’s to the tug of the pull-pin. To love that endures, to thriving without guilt, and to finally stepping into the life waiting on the other side.

Tom