Since I moved my newsletter from Mailchimp to Substack in January, a lot of things have happened. Not least, I have discovered where all the creative, deep-thinking people are hanging out, building thoughtful and supportive communities while the rest of the internet rages, posts clickbait, and finds new ways to hate themselves in the sea of political despair and filtered selfies.

There are many things that are wonderful about Substack.

I love that the app and website are ad-free, meaning I can be on a social platform without being bombarded by adverts for lip fillers (my age demographic), weight loss programmes (thanks, spy listening device I carry around in my pocket) and drop-shipped Chinese garbage I don’t need but for some reasons suddenly feel compelled to consider, wasting quarter hours like lawn sprinklers waste drinking water.

I love that Substack supports writers, whose incomes have been so enormously eroded by the internet, through Amazon’s royalty-crushing margins, the fractured attention spans that lower book sales, and the dominance of free content. I love free content myself (both giving and receiving) and have no immediate plans to introduce a paywall. But in the spirit of supporting Substack (which is great) and myself (massively improved on the earlier model) I am now turning on paid subscriptions. Free subscribers will still get full access to my weekly posts. But if you want to show appreciation for what I do through the time-honoured means of spendable tokens, I will repay you with pure, unadulterated, food-grade gratitude. The generosity of paid subscribers will not only encourage me when I am having a peanut morning; it will enable me to spend more of my time writing, which I hope we can agree would be a good thing.

One of the most wonderful aspects of being on this platform is that it inspires me to respond to other writers. This is where Substack becomes less of a newsletter portal and more of a literary salon. This beautiful piece about the author of Charlotte’s Web is the seed of this week’s post. I loved considering the importance of sensitive authors like E.B. White to produce literature that is a refuge and comfort for sensitive children (including future authors like me).

Though @susancain suggested we would not be surprised to learn E.B. White was “a shy, gentle & very private man”, I was astonished. I had always assumed E.B. White was a woman.

Charlotte’s Web was one of the most important books of my childhood so how did I get this so wrong? Maybe I knew that women sometimes published under their initials to improve their career prospects; for years, I considered doing so myself, but my first two initials, R.C., sound like an insult. (Though by nominative determinism, I did indeed become ‘Arsey Barber’. My very first review, in 1986, began ‘Ros Barber takes no shit.’)

But there was more to my belief that E.B. White was a woman. Charlotte’s Web is written with feminine-seeming sensitivities: its heroines are a young girl and a female spider who movingly gives birth to a large number of babies. (Yes, Wilbur, of course Wilbur, but we are focused through a girl’s love for him.) Whereas the males feel brutish: the father of the tale is happy to kill a baby pig with an axe.

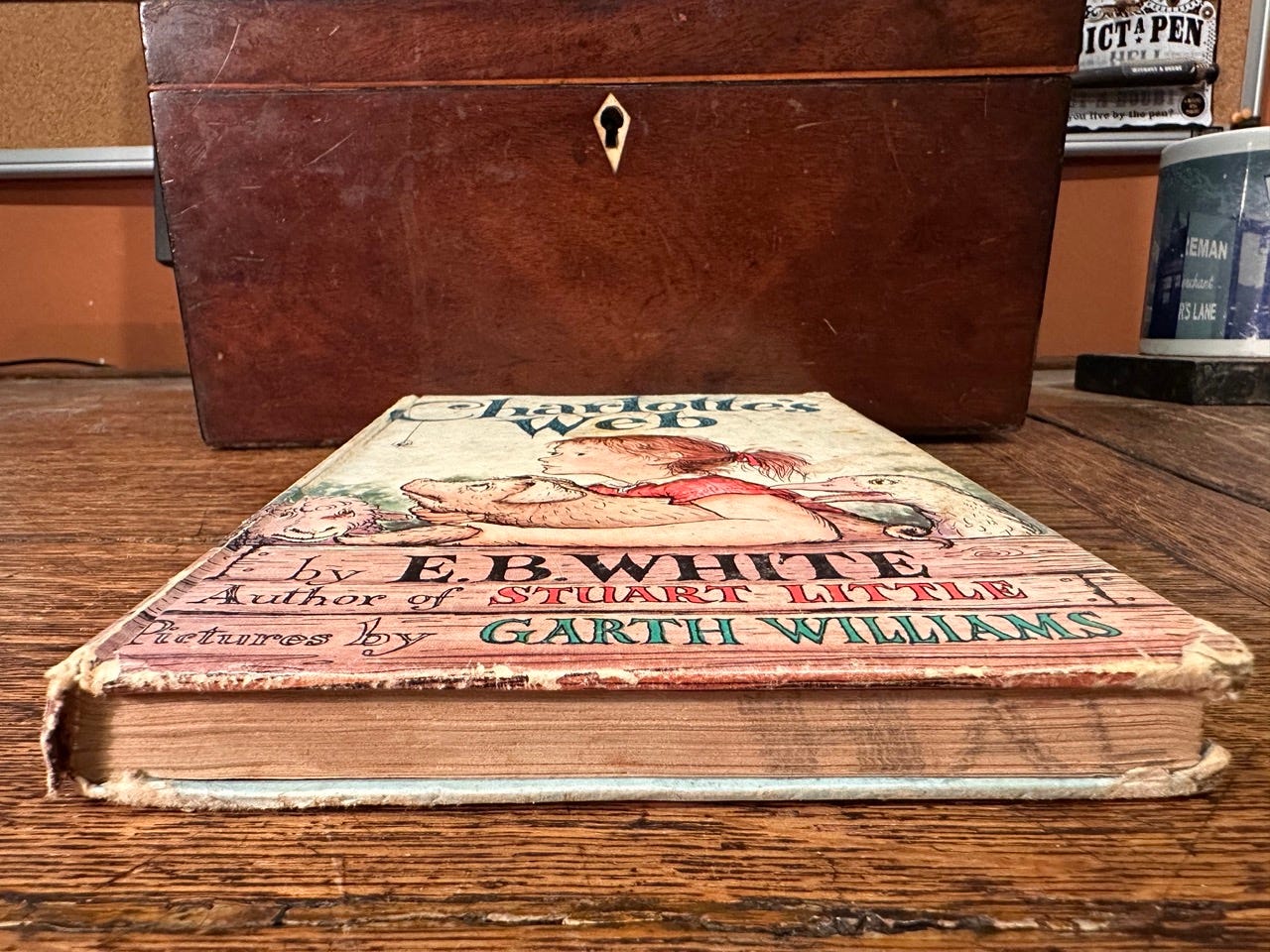

Charlotte’s Web became so beloved a book that I knew I would never dispose of my precious copy. I was so certain of this that, when I was six, I wrote on its pages something vitally important that I didn’t want to forget. And it turned out, that was the right instinct.

If you joined me last week for talk of epigenetics and double-blind random control trials etc., and you appreciate my background as a scientist-by-training and computer programmer, I need to ask you a question. Does your worldview count reality as purely physical? Are you something of a scoffer when it comes to things like (for example) out-of-body experiences? If you gave a resounding YES to both, I’d like to suggest that, to avoid an unnecessary dose of annoyance, you now stop reading. Cognitive dissonance is about as nasty as stepping on Lego in bare feet, so best to avoid. What I am about to divulge is only for the metaphysically-minded. I still appreciate you, though: please return next week, when I am planning to post a comedy rant about all the men who slide into women’s DMs. Thanks, bye for now, and if you liked this bit, do a quick scroll down and stroke the heart, because it genuinely increases the amount of love in the world, didn’t you know?* [*Not scientifically proven, but then hardly anything is. Everything is a hypothesis.]

»»»»>

Are we alone now? Are you ready for a little dose of goosebumpery?

Good.

Honestly, this is a genuine act of courage from me, because I know how it’s going to sound. But let’s go in through a door that is widely accepted.

Six was the age I was first rewarded for my writing (a box of Smarties from my headmistress). Also when I was six, like many other sensitive children, I had an invisible friend. I might have forgotten about my invisible friend except for one thing: I held onto my copy of Charlotte’s Web.

Through dozens of house moves. Through two breakdowns. Even through the flit required to leave my abusive first husband. I left behind a lot of stuff that day (including things I still think about, 26 years on) but I had the near-insane presence of mind to hang on to Charlotte’s Web. I was starting from scratch, but I still had this book. I almost didn’t know why. I just knew it mattered. I didn’t have any friends by then, to speak of. Abusive partners make sure of that.

But when I was six, my best friend was invisible. At the same time, he could not have felt more real. When our daughter was little, her invisible friend was a pirate called Smikey. He was real for her, too. Obviously, he wasn’t real for us, but we indulged her. We made sure Smikey had a chair at the table. When we found, behind a propped-open door, some food that she had left for Smikey (which he had, ungratefully, left to go mouldy), we weren’t cross. Invisible friends are real to the children that have them.

We can think them ‘invented’. But I remember very well when mine was not. He was no more an invention than David Cross, my best friend at primary school, was an invention. No more an invention than Germaine Greer or the Eiffel Tower. My invisible friend (who, like Smikey, had an unusual name, not Sally or Sarah or Steve) was with me, played with me, and talked to me. We had regular conversations. Which was what led to him, eventually, breaking my heart.

People were beginning to think I was weird. I mean, they weren’t wrong; if you keep talking to your invisible friend when you’re seven or eight, you’ll probably end up having additional weekly conversations with the child psychologist. But since the friendship was real, and very important to me, I was angrily resisting my parents’ insistence that I was “getting too old for an invisible friend.” My friend knew that these developments, if allowed to continue, weren’t going to be good for me. So he did that thing that truly loving friends do. He broke up with me for my own benefit.

I remember exactly where I was when this happened. He and I were under the dining room table, which had legs carved like big bunches of bananas. He told me he was leaving, but that I would be okay. Soon, he said, I would forget all about him. I was in floods of tears. I said no, I would never forget him, never ever ever!

But he vanished, and I was devastated. I felt abandoned and unbearably alone. Yet in what I’d said to him, I was determined. I would not forget him. I knew he probably had some mind-wiping magic (in the name of ‘helping me’), so I ran to my copy of Charlotte’s Web, and with a pencil, I inscribed his name on the edge of the pages. Not within them, in case, when I was an adult, I never opened it. But on what bookmakers call the ‘foot edge’. Reading the book, or casually looking at it, no one could see his name. Tucked into a bookcase, spine out, no one would be the wiser.

Roll forward nearly four decades.

I was writing The Marlowe Papers, an imagined alternative history where Elizabethan poet and playwright Christopher Marlowe didn’t die at the age of 29, but escaped to Italy with the help of his friends in the government’s newly formed Intelligence Service, continuing to write plays, using savvy businessman William Shakespeare as a front. Yes, that old chestnut, but with the added fun that I was writing it in the first person, in blank verse, as part of a PhD.

Only once my proposal had been accepted, and funded (thank you, AHRC) did I realise I was committing the most monstrous act of hubris. How on earth had it escaped my notice? I’d said I’d write a novel in the voice of an immensely gifted writer, who is, in that novel, the author of the GREATEST WORKS OF LITERATURE IN THE ENGLISH LANGUAGE. How on earth was I going to pass myself off plausibly as the author of Hamlet?

I froze. For three months. And then one morning, in desperation, I decided that it wasn’t me that was going to write this book. I mean obviously, how could I? There was nothing in my writing track record to suggest I was capable of such a feat. I knew who could do it, though. Kit Marlowe could do it. So I said, “Look, Kit, if you want your tale told, use me. You tell me what to write, and I’ll write it.”

If you’re not a writer familiar with this method, this might sound ridiculous, but I had a bunch of poems and short stories and three unpublished novels under my belt already; I had learned the art of listening to that “little thing in my head, sort of at the base of my skull, a kind of voice generator” (George Saunders) and knew how to surrender to the imagination.

Asking Kit Marlowe to write the book took all the pressure off me. Hell, all I had to do was turn up at my desk, get myself in the right state to ‘receive’ some words, and take dictation. No responsibility to create anything; just be the secretary. If it turned out crap, no worries, it was his fault. And if it was good, I’d get the credit. Which seems a pretty amazing arrangement, really.

So there I was, aged 44, some way in. I had (fictionally) developed the well-known suggestion that the first seventeen of Shakespeare’s sonnets were addressed to the Earl of Southampton, urging him to marry, a commission from Southampton’s guardian Lord Burghley, who wanted the young earl wed to his grand-daughter. Southampton (first name Henry) had, like E.B. White, certain ‘feminine’ qualities. He was also seventeen. He wasn’t interested in getting married. I was writing a ‘bi’ Marlowe and had him falling in love with this beautiful younger man, though, of course, Southampton, being a nobleman, was well beyond the dating pool of a cobbler’s son (and never mind the age gap).

Making connections between the imagined life and the works, I’d become conscious of the friendship, and later, the crushing dismissal, of tavern-loving Falstaff by the young Prince Hal when he becomes King Henry V. Kit’s friendship with Southampton seemed a parallel. In the novel, it all turns (first in deepening and then in destruction) on whether or not Kit is allowed to call him ‘Hal.’ Suddenly, goosebumps. A dim memory. Surely not.

Could it be possible? Did I remember that right? One thing I did remember; I had recorded that information.

I got up from my desk and went searching through my many, somewhat disorganised bookcases, looking for Charlotte’s Web.

And there it was.

++ If you liked this post, please light up the heart so more people can discover it.++

Sharing is also a wonderful way to support weird creative types who seem to be claiming they have some metaphysical connection to dead people, if you want to encourage that sort of thing, which, frankly, feels a bit irresponsible. Regarding that perennial question “Where do you get your ideas from?”, surely the answer is “huh?”

Post-it Notes

Since last week I have

Edited 16,000 words of the female pirate novel - nearly there!

Spent a lot of time thinking about setting up a micro garden office so I can save my eyesight

Turned on paid subscriptions in the hope of funding said micro garden office

Emailed a Bishop (and he emailed me back!)

Dug up two old research papers I am thinking of publishing

Tipped over the 1000 subscriber mark and grown another 100 subscribers this week. THANK YOU! I’m very appreciative of your readership.

I found this piece via @Susan Cain… as always, weird and beautiful is always my favorite writing to read. Thank you Ros… and thank you Hal 🫡

Wow! I also always assumed E.B. White was a woman - thanks for teaching me something new and the great read