Romans are buried in the garden. The house is built on a Centurion graveyard. Her stepfather, Colin, digging deep for vegetables, finds fragments of mosaic, a terracotta oil lamp. Normal for the Lexden area of Colchester, once Camulodunum, the Roman capital of Britain until Boudicca scared the colonisers to centre themselves fifty miles away, in what becomes London.

Boudicca, warrior Queen of the Iceni tribe, enraged by the gang rape of her virgin daughters, slaughtered every Roman in the town, and burned down the Temple of Claudius.1 The women of Britain were powerful. They inherited wealth and kingdoms. The Romans, when they invaded, brought male domination with them. Didn’t believe that women should rule, and lead. And when Boudicca’s husband died, they stole everything from her. Including her daughters’ mental health. Generational trauma begins here, in male violence.

East Anglia has a history of strong women. The Witchfinder General, Matthew Hopkins, started his witchhunt in Manningtree, ten miles away. He tortured independent, wise women in Colchester castle. Forced them to confess to things they hadn’t done, and had them killed. Before this “Christian” young man died in his mid-twenties, he’d killed a hundred of the area’s powerful women.2 The kind of women who resist being dominated. The kind of women who, therefore, have to be crushed.

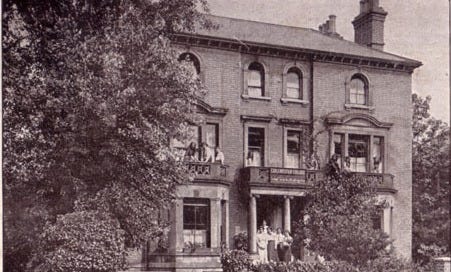

The house had been a girl’s school. Years later, she found a photograph online of girls in long skirts lined up on the steps; girls at the first-floor balcony of the kitchen where she had hung out and smoked with her friends as a teenager. These schoolgirls look well behaved. They probably got beaten.

Living there fifty years later was another education.

By the early Seventies, the two Edwardian townhouses had been separated and number fourteen was divided into bedsits. This is the house her stepfather buys and moves them into. Her mother, the prize. Her four children, the baggage.

The four-storey house is bought for a pittance with sitting tenants. The tenants leave one by one, apart from Mr Earl. He’s an elderly man with a smoker’s cough. In the middle of the night, she hears him hacking his way across the yard to the outside toilet. The yard which her parents want to make a patio. The outside loo they want to demolish and replace with a garage. Because of Mr Earl, the kitchen is upstairs, where Mr Bird’s kitchen had been, and remains there for the next fifty years. Mr Earl’s flat, on the ground floor, is due to be the living room and her mother’s longed-for music room. But Mr Earl refuses to leave.

Her stepfather puts a piano in the hallway, and pushes the back of it against Mr Earl’s wall. They are encouraged to play it loudly, and badly, and often.

Her stepfather is something of an expert at making people feel unwelcome. Once Mr Earl is out of the way – which takes almost a year – the focus is on them. Not that he presses them to renounce their tenancy. They are children, after all. But he puts them in the basement, and their mother at the top of the house, and between, several floors of antiques and untouchables.

The controlling regime is purely psychological, though it might not have been. Not long after she and her siblings move in, there is a smacking incident. Her six-year-old sister, eating cereal, has her hand slapped by Colin for holding the spoon “the wrong way”. The slap makes the spoon into a catapult: milk and cornflakes everywhere. Colin shouts at the infant girl for the mess he’s made and makes her cry. Her brother Peter tells their Dad, living in a bedsit two roads away. There is an exciting punch-up in the driveway. All four kids watch it from the living room window; their dad decking their stepdad.

Do they cheer? Does their stepdad hear them through the Edwardian single-glazed windows? After the punch-up, subtler methods are brought into play. And slowly, over the course of a decade, each one of them is broken. Her brother, fatally so.

She is eight when they move in. Their mother co-opts them — her, her older twin brothers, her younger sister — to paint kitchen furniture on spread out newspaper in the hallway. Furniture that her stepfather, ever one for a bargain, bought from the auction rooms. He is fond of the auction rooms. Later he’ll collect copper kitchenware on high shelves that she’ll be paid ten pence an hour to polish, and framed 18th-century maps of the local area, which line the townhouse’s several flights of stairs. For her mother, he’ll start collecting antique clocks. For himself, Japanese netsukis. Things you mustn’t touch.

In the early days, he brings home mostly cheap furniture, like the two kitchen cupboards. They paint one shocking pink and the other moss green. These are placed either side of the kitchen’s chimney breast. The green one on the left for his food. Anything expensive or unusual. Tinned lychees from one of his patients, the Chinese restaurant owner Mr Ho. The one on the right for their food: cereal and jam. In the left cupboard, brand names. In the right cupboard, bargains. In the left cupboard, Kelloggs cornflakes. In the right cupboard, Wavyline. His stuff. Their stuff. As she and her siblings help paint those two cupboards, the system she would come to know as Food Apartheid is born.3

Separation is the general theme. The house is large enough that the mezzanine floor out to the rear between the first and second floor has three rooms: a toilet and two separate bathrooms, now designated ‘adult’ and ‘child’. The child one is crammed in the middle, narrow and crummy; the adults’ is larger, with a stained-glass window. This is the pattern for a decade. Quality for the adults. The children don’t matter.

Her parents on the top floor: main bedroom, guest room, his study, and in the wide top hall, a butter-yellow sink in a vanity unit and her mother’s sewing table: the Singer machine you’d often hear going as she ran up a brand new outfit in gold lame or silver lurex: something split to the waist, ideally, for maximum cleavage or thigh. The Seventies were the party years.

In her parents’ bedroom, windows look over the long garden to the open air swimming pool of Colchester Royal Grammar School for Boys. As a teenager, she’ll sometimes go up there when her parents are out. She’ll stand at the dropped sash window, bathing in the summer screech of swifts. Bathing in laughing and splashing from the pool; the flash of white skin as then run out, and bomb back in. Looking for sight of anyone she knows Because she knows some of them by then, the Grammar School boys.

But at eight, she is learning what it means to be in this new family that isn’t a family. It is the doctor and his wife, Dr and Mrs, Colin and Viv, and some incidental children of hers who sleep in the basement. She is learning what it means to live in a home that isn’t a home.

Loud parties punctuate the months. A crate of Veuve du Vernay chilling on the front porch. Hoots and screeches. Dangerous clothing. Dancing — if that’s what you call synchronised jumping up and down to Status Quo — causes terrifying rhythmical bowing in her bedroom ceiling. For subsequent parties, they prop it up with a thick wooden beam.

Colin and Viv. Life and soul. Drinkers. Nudists. And she suspects now, swingers, or swinger-adjacent. Her brother catches Colin, in the guest room, fondling the breasts of her mother’s best friend (who is at the time, also her best friend’s mother). When she reaches the age her mother was then, Viv shares stories: how often, as she said goodbye at the doorstep, this or that husband would push his tongue into her mouth. She acts shocked, but she wanted them to want her.

Neglect was just how you raised kids back then. You sent them off to play and got on with your life. And in Mum’s case, she had a lot of life to catch up with. Getting married in the Fifties had been a mistake. She’d thought, as so many women think to this day, that she was loved for herself — a brilliant physicist with a First from Cambridge, a scholarship pianist, Viv for vivacious. And when she married her childhood sweetheart, the Adonis she adored, they were, everyone said, the perfect couple. She aimed to be brilliant at wifehood and motherhood too.

But how to bear having your brilliance crammed into the tiny airless jar of domestic servitude? Be shushed by my Dad, be told she was “too much” now she was his wife? Expected to play small, and dress down. In the midst of fascinating table conversation, be sent to the kitchen to be with the wives, not the physicists. This is why uncivilised countries deny women an education. Your equals make terrible slaves.

She asked me in my thirties, when I’d escaped my first marriage, "‘Why, once a man “has” you, do they want to crush everything that attracted them to you in the first place?’ Because those men are weak. They are scared of powerful women.

The Sixties unfolded, and four times, her belly expanded. Stuck behind a pram, she watched the sexual revolution explode. The women five years younger had freedoms she envied. Free love, you say? Boy, did she need some of that.

Bikinis arrived too late for her. All that time she had a great figure and skin, the one-piece ruled. Now, her body was scarred by twins, her stretchmarked stomach was a ploughed field. How she’d missed out! So when she broke up with dad and took up with Colin, a man who, for all his faults, let her be who she was, she jumped hard on that sexual revolution train. How she loved a bikini. The tinier the better. Crocheted them smaller than a shop would ever make them. Gold lame string. Lots of holes. The train of freedom was rattling ahead. She was trying to catch up, double-speed. And we kids, though she loved, we were just… in the way.

It was easy to turn a blind eye. We lived in the basement. And one of her eyes, symbolically, was in fact blind. She didn’t want to hear we were unhappy; she was finally happy. How we felt was irrelevant; we were kids. Kids are resilient, she said. After all, what were we suffering? They’d been kids in a war, with bombs dropping every night on the streets they lived in. We were just ignored. And treated like we didn’t matter of course. Like we deserved crap food. There was that.

Bad things happen when you dominate powerful women. When you force them into tiny little boxes where they truly don’t belong. Bad things happen for generation after generation. Not just to women. To men, too.

Imagine if Boudicca’s army had won more than the Battle of Colchester. Imagine the ancient Britons, who honoured women, had kicked out the Romans. Had resisted all future patriarchal conquerors. The Vikings. The Normans.

Imagine if the strong women of this Isle had clung on to their power. My mother (and millions like her) would not have been pressed into an unfitting, depressing servitude. She could have made discoveries beyond the kitchen. Advanced science. She wouldn’t have had to settle for a man who taught her kids they were worthless. She wouldn’t have lost a son and set me up for my own bad marriage. If strong women had held onto Britain. And not been brutally suppressed for two thousand years.

Yes, impossible to imagine. Brute force (which nature bestows on men through their musculature, after puberty) will win every time in uncivilised cultures. It’s easy to crush women when you pack a punch. When you can turn them into incubators. When you can hold their babies ransom. When you crush their thin necks with your greater handspan and grip strength.

But when, oh when, will we be civilised? When will we recognise that women are men’s intellectual equals? That no human beings, male or female, should be born into the expectation of servitude?

Tomorrow is International Women’s Day, and things are considerably worse for women than they were a year ago. So, my friend. What shall we do about it?

It has to start at home. A good home is an equal home. A home where every voice is heard and listened to. Where conflicting needs are accommodated. Where chores are parcelled out fairly. Where we help each other, respect each other, and give each other grace.

Though I’d use the word as shorthand — “going home” — that house in Colchester was never a home. Because home is where you belong. That house was the training ground for a lifelong sense of not belonging. Unwanted, rejected, pushed out. It’s a pattern that keeps forcing its way back into my awareness. Meaning I am still vibrating this childhood pattern, engraved into my soul for the decade I lived there and the next two decades until Mum died.

Home isn’t a place at all of course. It’s a feeling. We know it when we sense it. A place you feel safe. A place where you’re loved and appreciated for exactly who you are. Cleverness and all. Swearwords and all. Crocheted bikinis and all.

Me? I feel at home in the home I created, and Substack. Thank you, friend, for being here. Happy International Women’s Day. May all men one day understand how much better everyone’s lives will be when they stop trying to crush us.

💜 Like this? Then please LIKE this! 💜

If you’re looking for more IWD content, jump on this fiery piece from last year. It still has some juice in the tank and it’s a whole other vibe (fierce/funny).

If you want to join our wonderful community of readers, writers, and supporters, becoming free to comment and enjoy everything I offer, you can do so here:

Or if you can’t afford a monthly subscription, but want to show your appreciation, you can buy me a coffee. Which won’t go on coffee but will go on grocery bills!

Over to you

What was your parents’ parenting?

What historical characters or events are associated with the area you grew up in?

Did this affect you in any way?

Do you do anything particular on International Women’s Day?

Will women *ever* be treated as full human beings, or is that an impossible dream?

For more on Boudicca and her slaughter of Romans at Colchester, see https://www.historic-uk.com/HistoryUK/HistoryofEngland/Boudica-and-the-Slaughter-at-Colchester/

For more on Matthew Hopkins, the Witchfinder General, see https://www.discoverbritain.com/history/icons/mathew-hopkins-witchfinder-general/

For the lasting psychological effects of Food Apartheid, see Firehose Your Fears.

They used to say that the location of Boudicca's camp the night before she burned down Colchester was my school's playing field. I always loved that and when I was about nine, I wrote down a list of women who I felt our school's houses should be named after. For some reason, they were all men, despite the fact that I attended an all-girls' school.

So I suggested to my teacher:

*Boudicca

*Grace Darling (imagine rowing in a storm - in a *corset*!)

*Florence Nightingale

My suggestions were ignored. But I knew even at that age that I had my strong heroines who wouldn't be told what to do.

I was one of those Grammar School boys, in the eighties 😊